By transport writer, Mark Ovenden

The Royal Mail commemorated of one of the UK’s greatest works of visual information design last month when Harry Beck’s London Underground diagram was included for the first time on a British Postage stamp (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The current London Underground map on a 2009 stamp. ©Royal Mail

The importance of Beck’s rectilinear, topologic 1933 diagram (Fig. 2) is widely recognised by graphic designers and much praised by “wayfinders” (people evolving the discipline of signage and mapping the urban environment) as one of the greatest works of the 20th century.

Fig. 2 Beck’s 1933 diagram ©TfL/London Transport Museum

Fig. 3 1931 Berlin S-Bahn diagram. ©BVG

Map collector Peter B. Lloyd says Beck built on what went before: “…going back to the Underground Group's first modern-looking maps of 1908”. Beck’s earliest sketches for the diagram published by London Transport in 1933 were first prepared during 1931 – the same date the Berlin S-Bahn plan was printed. Though it’s not possible to know whether Beck saw this, it is unlikely he was aware of it – a case perhaps of great minds think alike? Dow’s diagrams were however widely available from 1929 and it has been documented that Beck was aware of these.

Fig. 4 Neat lines across Europe on an 1897 ‘diagram’.

Despite these forerunners, Beck’s contribution was impressive; the name of this electrical draughtsman has become an international byword for public transport schematics. His principles of neat 45 degree angles, elimination of topography and equalised station spacing have been emulated by urban rail map-makers from Atlanta to Zurich (as “Metro Maps of the World” showed). But the more interesting question is why Beck never extended his ideas outside London? The answer is he did. His attention was turned to the nearest major subway network to London: Paris.

Fig. 5 1930 topographic station wall map. ©RATP

Though a few examples of privately drawn diagrams have emerged (one Kandinsky-esque rhapsody in abstraction from 1939, so utterly bizarre and impractical that it was never repeated – Fig. 6 - plus a 1950s attempt by another British designer David Lawrence and several commercial offerings in the 1960s and 70s), schematics were not adopted by the RATP until the last years of the 20th century.

According to Ken Garland’s excellent history (“Mr Beck’s Underground Map”) the Paris Metro operator approached Beck to design a diagram. Garland supposes the work was begun in the late 1930s but not finished until after the War. Garland shows that Beck included station name changes which happened after the War but left on some pre-War service patterns. Little survives of this first attempt except a lone monochrome copy in Garland’s collection (Fig. 7).

The Paris Metro is not as easy to simplify as the London Underground. Firstly the lines interweave with each other more (Ligne 7 the snakiest of these customers); this gives rise to more interchanges (by 1933 around 40 in London, 50 in Paris, depending on what one defines as a proper interchange between lines). Also the system was then mostly hemmed-in by the old Paris walls (a distance equivalent east-west to the width between South Kensington and Canary Wharf and north-south between Camden and Brixton). With 200 plus stations in easy reach, this is great for passengers, but more challenging for map-makers! One of Beck’s greatest innovations was to massively expand inner London and condense the outer suburbs. This was just not needed in Paris (at that time) because the entire system was already in the ‘centre’ and very few stations in the suburbs.

Given he had an entirely free hand, and standing on the shoulders of his own and other people’s diagrams, what Beck therefore tried for Paris was in some ways more radical than what he’d achieved for London. He sought in the mass of interlinked lines some key visual axes to give his diagram order. Seizing the east-west running Ligne 1, Beck made it his prime axis (not as in London’s Central Line, running horizontally, but at that neat angle of 45 degrees). He exploited something seen unnoticed by previous cartographers: Lines 2 and 6 form a rudimentary circle. Beck transformed them into a rectangle with rounded edges. From these roots he plotted the other lines as straight as possible with impressive results: the curvaceous Ligne 10 becomes a flat line with its odd one-way loop stylised at extreme left. Kinky Ligne 14 is straightened to a single stroke. Ligne 3 – often seen on other maps with up to 11 direction changes – is reduced to just one nicely rounded alteration.

The overall appearance is clear, balanced and arguably easier to follow. However the key question was: would the French like it? The answer when Beck presented his first version was a resounding “NON!” Beck was not easily deterred. Indeed his first London diagram was also rejected but he persisted and eventually its adoption, adoration and appositeness for the Underground was widely applauded. The same fate was not to befall Paris.

Beck went back to his drawing board and produced a second version (dated as 1951, Fig. 8). It’s not known if this was commissioned but luckily for us it survives in full colour and was recently revealed as one of the attractions at the refurbished London Transport Museum. It was published for the first time in a book when “Paris Metro Style in map and station design” came out in November 2008. Like any inspired genius, Beck did not waver from his initial concept: here again were his two original axes but Ligne 4 is simplified in its northern half. There are 15 physical direction changes in Ligne 7 heading towards almost every compass point; Beck whittled these down to just two. Ligne 8’s 14 real bends come down to two, Ligne 11’s 8 real turns cut to none….and more visually impacting, Beck has with great wit added the River Seine.

So why did the Paris Metro – now operated by the RATP – reject Beck’s clear simplification of their beloved system? One reason is visible at each station entrance; Parisians use the maps here as a free public service to help them find their way round the city – the ubiquitous geographic wall map is more than just a Metro plan. The French adore pure cartography – laying claim to many mapping firsts, not least of which were colonial maps of the newly discovered lands in North America and Cassinni’s magnificent Carte géométrique de la France– a topographic map of the entire country (begun in the 1670s, though not finished until a century later). The painstakingly precise 1739 Turgot map of Paris (a kind of 3D view from the air, purported to show every visible window) is legendary.

Aside from cartographic history though, Roberts argues there was a fundamental problem with Beck’s Ligne 1 axis: “Paris is on a slant. Line 1 especially…at roughly 25 degrees to horizontal. For a traditional diagrammatic map, which angle should it be snapped to? Horizontal or 45 degrees? Whatever angle [is chosen, results in] at least one of the following problems: (1) uneven use of space as lines are compressed together or stretched apart more than in reality; (2) lots of kinks for trajectory correction to avoid (1); or (3) lots of geographical distortion”.Roberts suggests Beck’s omissions on both versions (Gare de Lyon missing and Montparnasse drawn wrong on the first and both Edgar Quinet and Vavin stations missing on the 1951 version), led to suspicion that the concept was untrustworthy. Though many contemporary Paris Metro maps also contained errors, some going uncorrected for years. In his fascinating critique of Beck’s work (at www.tubemapcentral.com) Roberts postulates powerfully that though Beck’s diagram has aesthetic qualities it distorted well-known Parisian geography too much for comfort. This is a city which took its twenty arrondissements to heart far deeper than Londoners ever appreciated their postcodes or boroughs.

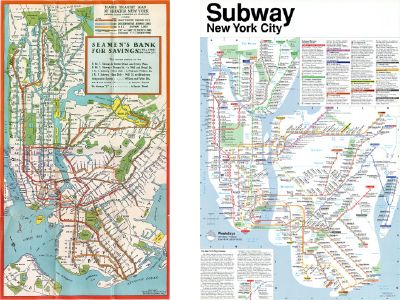

Also diminishing a diagram’s benefits are the closeness of the stations to each other; one can be plonked down blindfolded in virtually any Paris quarter, walk 500m in any direction and theoretically bump into a Metro entrance. Although in practice there are several holes in the system, such station spacing is much denser than in any other city in the world; a feat the French are justifiably proud of. But pride may be the true reason for the operators’ disinclination towards Beck’s or anyone else’s diagrams. By mid century Beck’s London diagram was ubiquitous and it was beginning to catch on: Sydney’s rail network was depicted in Beck style from 1939 (when a pocket map was issued on an identical sized folded card even aping the London Underground roundel on the cover). New York had its first Beck-esque diagram by 1958, Boston by 1967, Moscow & Osaka: 1970, Saint Petersburg: 1971, Hamburg, Munich and Tokyo: 1972, Melbourne, Montreal & Glasgow: 1976….etc

In staunchly proud Paris, despite the multi-coloured spaghetti with which most contemporary maps had portrayed the Metro, there was opposition to following Britain too closely. Double-decker buses for instance – though tried out in the 1960s – were not thought suitable for the Paris streets at least partially because they resembled too closely the ambiance of the British streetscape. In addition, a 1934 pocket Metro map by F. Lagoute, introduced a style that essentially lasted almost forty years: though it fell short of standardising angles and was occasionally redrawn, its clarity and geographical reflection of the city was sufficient for Parisians not to complain – a behaviour which they normally have few qualms in partaking (Fig.10).

Fig. 12 The Paris region’s rail services as a single diagram. © RATP

· Becks 1951 diagram has been redrawn by Max Roberts who has re-coloured it to match the line colours used on official maps of the day. It’s available as a poster from www.afterbeck.com

Further reading:

· “Paris Metro Style in Map and Station Design”. Mark Ovenden. ISBN 1-85414-322-0 (reviewed in CR January 2009)

· “Pari Underground - The Maps, Stations and Design of the Metro". Mark Ovenden. ISBN 01-4311-6398

· “Mr Beck's Underground Map”. Ken Garland. ISBN 1-85414-168-6.

· “Underground maps after Beck”. Max Roberts. ISBN 1-85414-286-0

· “Metro Maps of the World”. Mark Ovenden. ISBN 1-85414-288-7

· “Telling the passenger where to get off”. Andrew Dow ISBN 1-85414-291-7

· “No need to ask”. David Leboff and Tim Demuth. ISBN 1-85414- 215-3